Power struggle for Hughes’ empire reached epic proportions

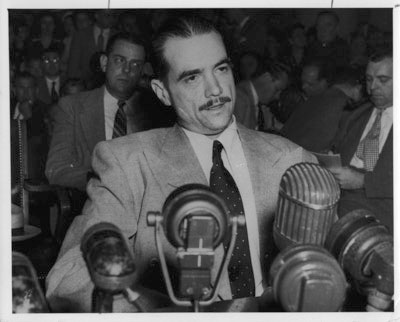

Editor's note: "Howard Hughes: Power, Paranoia & Palace Intrigue" by Review-Journal columnist Geoff Schumacher (Stephens Press) probes the reclusive billionaire's activities in Las Vegas and his lasting impact on the city. The book touches on all aspects of Hughes' multifaceted life, but focuses on the years 1966-1970, when he confined himself to a suite on the ninth floor of the Desert Inn. The following excerpt chronicles the physical and mental decline that characterized Hughes' tortured final years.

Howard Hughes lived one of the most interesting and varied lives of the 20th century, yet the public's fascination continues to turn to the final years of his life when he took an epic mental and physical nose dive and his lieutenants went to war over control of his riches. With the deterioration of Hughes' condition in his last years, he no longer was able to dictate the course of day-to-day affairs of his many business enterprises. And executives working for Hughes had different ideas about how things should be done -- and who should run the empire.

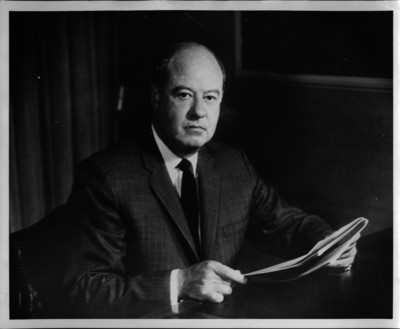

As Hughes gradually descended into darkness and drifted to the sidelines, top executives battled for control. Initially, Hughes entrusted Bob Maheu, based in Las Vegas, with primary decision-making authority. This move frustrated longtime Southern California executive Bill Gay, who felt he should be in charge. Meanwhile, New York attorney Chester Davis, too, had a large role in Hughes' affairs, especially his long-running legal battle over Trans World Airlines.

Maheu maintained a high profile, buying casinos and land in Las Vegas and handling political matters in Nevada and Washington, D.C. But Gay still controlled the coterie of aides who responded to Hughes' every want and need. Gay also controlled the doctors who cared for Hughes and provided him with a steady supply of pain-killing drugs.

Gay's control of the so-called Palace Guard gave him a distinct advantage when he and Davis made their move against Maheu in 1970. Evidence and testimony strongly support the contention that Gay and the aides persuaded Hughes to act in certain ways by increasing and decreasing his drug supply and censoring the information he received about his business affairs. They poisoned Hughes' relationship with Maheu, resulting in his firing, and talked Hughes into fleeing Las Vegas to avoid a legal confrontation with Maheu.

"They started telling him I was trying to steal his empire," Maheu recalled in a 2007 interview. "They were telling him I had either filed or was getting ready to file a lawsuit trying to gain control, which scared the hell out of him."

Hughes turned over control of his business affairs primarily to Gay and Davis. Ultimately, Gay, Davis and the Palace Guard allowed Hughes' health to continue to deteriorate because this allowed them to run the companies without his interference.

One of the most straightforward summaries of this period of Hughes' life is contained in a legal memorandum filed in 1980 by the Hughes estate. The motion pulled no punches in outlining "an extraordinary scheme perpetrated upon Hughes and his companies by the 'Palace Guard' which surrounded Hughes for the last 10 years of his life. These individuals ... are charged with having seized control of Hughes' empire and having enriched themselves at Hughes' expense. They are alleged to have done so, in large measure, by taking advantage of Hughes' drug addiction, seclusion and mental incompetency to run Hughes' enterprises -- ostensibly in his name, but in fact for their own personal benefit -- and by manipulating and controlling a virtually helpless Hughes."

According to the motion, the conspiracy scheme began while Hughes was secluded in the Desert Inn. "As in most conspiracy cases, many of the actions committed by the defendants may seem innocent in and of themselves. It is when they are taken in context that their role as integral parts of a wrongful scheme becomes apparent. ... And when the evidence is viewed as a whole, it points directly to the conclusion that the defendants, their conclusory denials notwithstanding, did indeed conspire to gain control of Hughes' empire and to use it for their own advantage."

The motion argued that Gay, along with Nadine Henley Marshall and Kay Glenn, controlled the aides who surrounded Hughes. It contended they "served as a virtually impenetrable barrier between Hughes and the outside world, screening nearly all incoming and outgoing messages."

"Gay used his power over the aides to direct them not to deliver messages to Hughes which Gay did not want Hughes to receive and not to transmit Hughes' messages to others which Gay did not want transmitted. Aides who refused to follow these procedures were severely criticized by Gay, Glenn, or Henley Marshall, as well as by other aides." Further, the memo contended they "cruelly took advantage of Hughes' physical and mental disabilities, his drug addiction, his eccentricities, and ultimately, his mental incompetency to help themselves to Hughes' wealth."

One form this took: "lifetime contracts" for selected executives, guaranteeing they would receive a regular paycheck from Hughes in perpetuity. As for Davis, he billed Hughes large sums for his legal services.

They controlled Hughes in large part by manipulating his drug addictions, according to the motion. "Beginning in 1961, and throughout the four years in Nevada, Dr. Norman Crane supplied Hughes with codeine and Valium. He did so by writing false prescriptions in the names of the aides, primarily John Holmes, but also (Levar) Myler, (Roy) Crawford and (George) Francom. After Crane wrote the prescriptions, Holmes obtained the drugs and delivered them to Hughes in Nevada."

"Hughes regularly was under the influence of codeine, Valium and other drugs throughout the Desert Inn period," the memo stated. "He injected himself with codeine using syringes kept in a small metal box in the refrigerator in the aides' quarters outside his room." Indeed, Holmes and Crane were later convicted of conspiring to distribute codeine to Hughes.

The memo noted that Hughes' mental behavior also became stranger during the Desert Inn years. "Throughout the Desert Inn period, Hughes' behavior suggested severe mental problems as well. He was totally nude almost all of the time, only occasionally wearing a pajama top. He demanded that the windows be draped or closed and indicated no awareness of or concern with what the date or time was.

"Hughes required the aides to perform a series of bizarre rituals, many of which related to his unnatural fear of contamination by germs. He demanded that everything delivered to him be wrapped in Kleenex, and had a procedural manual which dictated among other things the specific numbers of Kleenex to be used for various actions. Other procedures were prescribed for washing one's hands, carrying and opening a can of fruit, etc. This fear of germ contamination was particularly anomalous when contrasted with his lack of personal hygiene and his use of an unsterilized syringe and needle to self-inject himself with large amounts of codeine."

The memo argued that Hughes led a very unhealthful lifestyle. "(His) physical condition also was appalling when he came to Nevada. He never brushed his teeth and had a foul breath odor. He seldom took a bath or shower. His hair was approximately shoulder length and his beard went down to approximately his chest. His eating habits were very poor. He was seriously underweight. He spent most of his time in bed, often staring blankly ahead, especially after taking large amounts of drugs. He often slept for lengthy periods, sometimes as long as 24 hours at a stretch. He suffered from chronic and severe constipation, often going two weeks without a bowel movement and requiring frequent enemas. When he did go to the bathroom, he often spent long periods of time there -- as much as 12 hours."

In 1968, about two years after Hughes moved to Las Vegas, Gay approached Maheu twice about having Hughes committed and assuming control of his empire. Maheu refused to cooperate with the scheme.

Unable to team up with Maheu, Gay decided to poison Maheu in Hughes' eyes, according to the legal filing. During 1970, Gay began to limit Maheu's access to Hughes. "Gay, directly and through Glenn and Henley Marshall, directed the aides to withhold Maheu's messages from Hughes. As a result, Maheu's messages piled up without being delivered. ... By late 1970, Maheu lost direct telephone contact with Hughes."

About that time, Hughes turned over control of the TWA litigation to Maheu, and Maheu fired Davis. "This set the stage for a power struggle which culminated with Davis and Gay seizing control of Hughes' empire," the memo stated.

On Nov. 14, 1970, Gay and Davis obtained a proxy giving them nearly unlimited control over Hughes' Nevada operations. "At the time the proxy was obtained, Hughes was seriously weakened from the second in a series of bouts of anemia, complicated in November 1970 by pneumonia," according to the memo.

Dr. Harold Feikes testified that in 1968 Hughes was "critically ill" and anemic enough to be on the verge of heart failure. Dr. Crane later described Hughes as having "nearly died" from the 1970 bout of pneumonia. Hughes required frequent blood transfusions.

According to the motion, drugs used by Hughes shortly before the proxy "soared to among the highest levels of his life." "The Nov. 14, 1970, proxy is a curious document indeed," the motion explained. "It gave Gay and Davis, acting together, absolute power -- certainly a strange act from one who had expressed his dislike for Gay and who had authorized Maheu to fire Davis just a few months earlier."

"Proxy was procured by undue influence," the memo stated. "Davis used the proxy to get rid of Maheu, lest Maheu get rid of Davis. And Gay, too, was threatened by Maheu's rise to power."

With the proxy in hand, Gay and Davis persuaded Hughes to move out of Nevada, presumably so he wouldn't have to testify if Maheu challenged the proxy. On Nov. 25, 1970, Hughes secretly flew from Las Vegas to the Bahamas. "He apparently had been convinced by the aides that it was necessary to leave to avoid a confrontation with Maheu," the memo stated.

Maheu was fired on Dec. 3, 1970, and Gay and Davis traveled to Nevada to take physical control of Hughes' operations. Maheu filed a court action challenging his removal, but he lost, in part because Hughes was beyond the reach of the court's subpoenas.

Over the next six years, Hughes lived in numerous locations. The Bahamas: November 1970 to February 1972; Nicaragua: February 1972 to March 1972; Vancouver: March 1972 to August 1972; Nicaragua: August 1972 to December 1972; London: December 1972 to December 1973; the Bahamas: December 1973 to February 1976; and Acapulco: February 1976 to April 1976. He died on an airplane that left Acapulco headed for a hospital in Houston.

Although Gay had succeeded in removing Maheu, he faced one more obstacle to total control: Hughes Tool Co. executives in Houston. In order to achieve this, he sold the tool division in 1972, supposedly to raise money to settle the TWA litigation. Ironically, just days after the sale, the U.S. Supreme Court reversed the judgment and dismissed the case. In December 1972, Gay and Davis achieved total control. They filled the new boards of directors with their people.

Hughes' fragile health suffered another blow in August 1973 when he broke his hip. Dr. William Young, who X-rayed the hip, described Hughes' condition "as being in a stage of malnutrition comparable to that of prisoners of war in Japanese prison camps during World War II."

The billionaire never walked again. "For the rest of his life, he was bedridden and emaciated, with a body weight of approximately 100 pounds, although he was originally 6 feet 4 inches tall," the memo stated. "He had increasingly long periods of unconsciousness, up to a day or more, and his days were spent sleeping, sitting in a semi-stuporous state or watching movies, some of which he had seen dozens of times before, often dozing in midfilm. He was totally out of touch with the outside world and his business affairs. The aides continued and, indeed, encouraged his isolation."

At this point, at least two doctors had determined Hughes needed greater medical care than he was getting while sequestered in dark hotel rooms. Dr. Raymond D. Fowler testified that Hughes was mentally incompetent by August 1973. And in April 1974, Dr. Norman Crane refused to continue supplying drugs to Hughes.

But instead of admitting Hughes to a top-flight hospital where he could receive proper care, Gay and Davis had another solution: They brought in Dr. Wilbur Thain, Gay's brother-in-law from Logan, Utah, to supply the drugs, which he did until Hughes' death. In return, Thain was offered an employment contract and a high position with the Hughes medical institute.

Thain also helped to negotiate lifetime contracts for select employees, in part by threatening to withhold drugs, according to the memo. Summa Corp.'s board of directors approved these contracts in September 1975. "The evidence ... shows that Thain mercilessly manipulated Hughes, forcing him to give employment contracts to most of the defendants, not to mention himself, as the price of the drugs to which Hughes was addicted," the memo stated.

Gay and Davis came across another potential foe in 1974 when Hughes' longtime friend, Jack Real, was gaining a measure of influence with the billionaire and attempting to help him out of his mental and physical prison. In 1974, after Hughes suggested that he wanted Real to have substantial power in running his businesses, Gay and Davis instructed aides to isolate Real from Hughes.

"They literally locked Real out by changing the locks to the aides' office -- which led to Hughes' room -- without giving Real a key," according to the memo. "They held messages from Hughes to Real and from Real to Hughes. When Hughes asked for Real to visit him, the aides falsely told him that Real was unavailable."

After taking control of Hughes' businesses, Gay, Davis and others began to feast at the trough. "Beginning at least as early as 1970, the defendants and their co-conspirators in fact treated themselves to lavish salaries, charged Summa with enormous personal expenses, and treated the company's aircraft, employees, houses and other assets as available for their personal whim," the motion stated.

In 1972, Gay's salary was $111,000. In 1973, after taking control, his salary climbed to $412,000. Aides who essentially performed secretarial and nursing duties received salaries of $70,000 to $100,000 -- huge sums for the time. Why? Essentially, they were paid not to talk about Hughes' drug use, according to the memo.

In addition, they used corporate aircraft for personal trips. Gay and Davis, for example, flew to Europe in 1972 to find Hughes a new residence. "While there, they chartered a private jet and flew to Nice, France, to meet Gay's wife; to Zurich to look at a watch for Gay; and to Majorca so that Davis could visit his daughter there," the memo charged. Two houses in Miami were purchased and used by executives "for personal pleasure," according to the memo. Substantial improvements were made to Davis' offices in California and New York at Hughes' expense.

The legal memo also outlined Gay and Davis' mismanagement of Summa Corp.'s Las Vegas casinos. "Neither Gay nor Davis had any experience in hotel or casino management, and apparently neither exhibited any understanding of the unique nature of the problems involved," the memo asserted. Gay, for example, "was personally involved in the hiring of entertainment" and imposed "arbitrary rules resulting in an inability to hire top entertainers for Hughes' hotels. As a result, the showrooms in these hotels were not filled and their revenues suffered a substantial decline."

Gay also allegedly mismanaged a Desert Inn expansion project, resulting in additional costs of $30 million. "He never had a comprehensive plan for the construction," the memo stated. "Rather, it was constantly being changed, depending on his whim. ... At one point, Gay decided that one of the new buildings, which already had been topped out, should have an extra floor, on which he planned plush suites for himself. The building was altered to add the additional floor at a cost in excess of $1 million."

After Hughes' death in 1976, the Gay-Davis empire crumbled with the arrival of Hughes' cousin, Will Lummis. Lummis assumed control of the estate and eventually got rid of Gay, Davis and the other alleged conspirators in his cousin's demise. The memo cited in this chapter listed Lummis as the lead plaintiff.