Viva Las other Vegas: New Mexico town leads slower life far from Strip

Las Vegas, meet Las Vegas. It's the least we can do for a city whose recognition gets obliterated by our marketing efforts.

Most of us know that New Mexico has a city with our name (although this knowledge may only owe to the occasional website daring to ask which Las Vegas we're referring to). Information about the other Las Vegas is scarce, however, because what happens there really stays there -- unless you type "NM" in your Google search.

This northern New Mexico hamlet -- situated between the Great Plains and the Rocky Mountains -- is home to three colleges, a museum, an arts district and 15,000 other people who call themselves Las Vegans.

"We're a family town, not a gambling town," says Las Vegas, N.M., Mayor Alfonso Ortiz Jr., who ran unopposed in the last election and who manages to navigate between city functions entirely without showgirl assistance.

"We like peace and quiet here," Ortiz says, adding that fewer than 10 daily flights originate from Las Vegas Municipal Airport -- all small planes and private or military jets.

Correction: It's our city that has their name. The pioneers of New Mexico's Las Vegas were the first to go by the Spanish translation of "the meadows," in 1835. (We waited until 1905.) And theirs was a bigger city than ours for nearly a century.

"What your Las Vegas is now, we were to the Southwest when America took over the territory from Mexico," says local historian and author Marcus Gottschalk. "If you mentioned 'Las Vegas,' people assumed you meant this Las Vegas."

The tables turned right around World War II, when our expansion because of Hoover Dam met up with their contraction because of the diversion of the Southwest's main railroad artery. (Since about 1950, their population has not increased.)

Not only was theirs the earlier Las Vegas, it was the earlier city of sin. In 1879, according to Gottschalk, gunslinger Doc Holliday owned a saloon adjacent to the brothels on Center Street, and outlaw Jesse James rolled through town twice. During one of these visits, Gottschalk says, James met Billy the Kid at a defunct hotel called the Old Adobe. (James considered relocating his train-robbing operation to New Mexico from Missouri, but it never happened.)

Crime is no longer one of their city's distinguishing characterics. According to Police Chief Christian Montano, murders never number more than eight per year (although, last year, our Las Vegas logged a much safer eight murders and nonnegligent manslaughters per 100,000 residents).

"Crime is about average for a small town," Montano explains.

The primary employer in their Las Vegas, which serves as the county seat of San Miguel County, is New Mexico. State workers are split mostly between the hospital (the New Mexico Behavioral Health Institute) and government offices including the Department of Motor Vehicles. Tourism, via the city's 14 hotels and motels, is best described as a steady trickle that the Las Vegas Chamber of Commerce would like to grow. According to the Chamber's Beth Carter, the City of Las Vegas Museum houses the largest collection of Teddy Roosevelt Rough Rider memorabilia anywhere.

"Well, I'm not sure about anywhere," she adds, "but we have quite a bit." (The future president and his famous Army buddies held their first reunion around town in 1899.)

Other tourism hot spots include the national wildlife refuge, Montezuma Hot Springs and the remains of Fort Union, built in 1851 to protect the Santa Fe Trail against Native American attack. (None is in Las Vegas, N.M., proper, but no other city is closer.)

According to Carter, the chamber is considering a city slogan, to be advertised in New Mexico Magazine and in travel periodicals circulated in Arizona, Colorado and Texas. The leading candidate so far: "the OTHER Las Vegas."

Living in our neon shadow can be frustrating. Misdelivered mail is the most common peeve.

"We order stuff and you get it," says David Lobdell, an art professor at Las Vegas' Highlands University with an unpleasant experience involving foundry equipment.

In general, though, New Mexican Las Vegans deal just fine with the anonymity we impose on them.

"People here are kind of happy to be here and not to be in your Las Vegas," says Martin Salazar, managing editor of the Las Vegas Optic, a 4,200-circulation newspaper that published daily from 1879 until 2009 (when it went to three days a week because of the economy).

"It amuses us," adds Mykle Williams, guest services manager at the Plaza, the city's $79-per-night Bellagio equivalent.

Williams says he doesn't mind the two or three out-of-towners a day who misdial the hotel, trying to book gambling vacations -- or the one or two a year who actually follow the exit sign off Interstate 25 in a state of confusion.

"They ask us where all the casinos are," says Williams, who usually smiles and informs them to drive another 700 miles. (Williams says he can't recall anyone ever pumping their fists or shouting "Vegas, baby!" while entering the Plaza.)

Interestingly enough, while this article was being researched, the Vans Warped Tour website mistakenly listed their Plaza Hotel's parking lot, not ours, as the site of its June 30 performance. (The mistake was quickly corrected.)

Although Las Vegas, N.M., lacks gaming and enough people to support an extreme sports/music festival stop, it does have a strip. Grand Avenue boasts historic hotels such as the El Fidel and Palomino and fine eateries such as Original Johnnie's Kitchen and Mary Anne's Famous Burrito. It even has its own MGM Grand-like lion, a stone sculpture at the intersection with Lincoln Street. And, while there are no Cirque shows, there's one humdinger of an annual July Fourth parade called the Fiestas.

Incidentally, this was the Las Vegas strip that gave birth to the Maloof dynasty. Early last century, Joseph George Maloof opened a general store on Grand after settling there from Lebanon -- according to his grandson, Palms owner George Maloof. The money earned from this store led to a Pabst beer distributorship, which led to a Coors distributorship, both in New Mexico, which eventually led to the Sacramento Kings and "The Real Housewives of Beverly Hills."

"Everything began there for my family," says Maloof, who was born in Albuquerque and says he gets back to the other Las Vegas "every once in a while," but has "no plans" to move the Kings there.

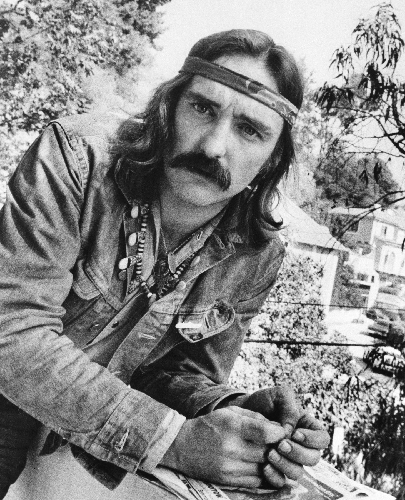

Those who assume that Las Vegas, N.M., is devoid of other pop-cultural relevance assume wrong. When Dennis Hopper and Peter Fonda got arrested for "parading without a permit" in 1969's "Easy Rider," it was filmed on Bridge Street. More recently, the Coen brothers shot 2007's "No Country for Old Men" almost entirely around town.

And celebrities don't always leave when films wrap. Patrick Swayze fell so in love with the city while making 1984's "Red Dawn," he bought a 2,000-acre ranch about 10 miles away. (His ashes were reportedly scattered there after he lost his battle with pancreatic cancer in 2009.)

"His splendor wore off with us," says Williams, who served as Swayze's "Red Dawn" stand-in. "He just became another Vegan, like everyone else." (Residents sometimes leave out the "Las" when identifying themselves.)

Currently, another movie star resides about 30 miles from town on a 5,000-acre ranch. Val Kilmer's splendor has worn off, too, but for a different reason. In 2003, Rolling Stone magazine quoted him as calling his neighborhood the "homicide capital of the Southwest" and referring to 80 percent of his neighbors as "drunk."

Since then, Kilmer -- who, coincidentally, played Doc Holliday in the 1993 movie, "Tombstone" -- has stopped attending Las Vegas basketball games and mostly keeps to himself.

"People have kind of lost respect for him," Williams says.

Las Vegas, N.M., is not a wealthy town. Per capita income in 2000 (the last year for which statistics are available) was $12,619, compared to $21,587 nationally and $22,060 here.

But that's precisely why, according to Ortiz, his Las Vegas has weathered the recession more successfully.

"We've experienced being poor," he explains.

Ortiz has heard about our record foreclosures and unemployment, and has some advice.

"Be down-to-earth people and realize that there are prosperous times, and there's also times when you have to tighten your belt," he says. "You don't know when those times will come, so you always have to be prepared."

Contact reporter Corey Levitan at clevitan@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0456.