Poor residents take brunt of planned Vegas Muni Court payments

Las Vegas Municipal Court officials are good at determining who owes them money.

They’re not nearly as good at figuring out why people didn’t pay in the first place.

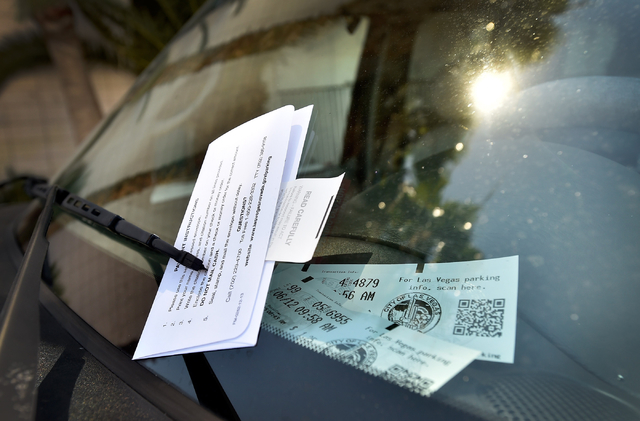

Court officials make little or no discernible effort to find out who can afford the court’s average $300 to $400 fine, usually charged for small-time property and traffic crimes ranging from trespassing to speeding.

Apart from those who have spent $50 to enroll in court-provided financial counseling, officials don’t keep any records of defendants’ income or ability to pay.

That leaves the task of separating those who don’t pay from those who can’t pay to the court’s six elected judges and two traffic commissioners.

A Las Vegas Review-Journal analysis of nearly 39,000 court payment plans approved by those judges found residents in the city of Las Vegas’ seven poorest, statistically black and Hispanic ZIP codes account for nearly two-thirds of those currently in hock to the court.

The court has collected at least $2 million in installment payments from those residents since 2009, compared to just a few hundred thousand dollars picked up in the city’s whiter, more affluent areas.

Those making payments to the court have spent an average of almost three years trying to pay down what they owe on an initial misdemeanor, parking or traffic offense. On average, three-fourths of them will miss a payment and pick up a warrant that could prove a one-way ticket to jail.

Current and former Las Vegas employees, who asked not to be identified for fear of retribution, say the city is treating its poor and minority residents like a cash machine. They say the court’s “money hungry” approach to misdemeanor warrants prioritizes cash above public safety and pressures marshals to take a credit card payment in lieu of locking up even violent offenders.

In other words, those struggling to make a traffic court payment shouldn’t expect relief anytime soon.

COURT TV

Court officials fought hard to preserve the right to threaten defendants with jail time during state legislative hearings in April. Often, it’s not an idle threat. Municipal Court judges sentenced more than 100 people to jail last year. Some had done nothing worse than letting their driver’s license expire, forgetting to renew their vehicle registration or letting their car insurance lapse.

Judges don’t set state-mandated court fines charged for those offenses, but they could lower court fees tacked onto the state’s fines or reduce minimum monthly payments owed by those who can’t afford to immediately pay a fine.

They also could stop scheduling jailed traffic offenders for a first, televised appearance in front of a traffic commissioner — a practice critics have called unconstitutional.

But the court doesn’t sound interested in making either of those moves.

Chief Judge Bert Brown said it’s perfectly legal to let traffic commissioners preside over in-custody TV appearances, though he couldn’t provide a reason why the court would need, or want, to do so.

Asked about the former issue — whether judges could do anything to help, or at least stop jailing, thousands of people who spend years trying to pay down money owed to the court — Brown sounded equally unmoved.

“I don’t think our fines are exorbitant,” the four-term judge said. “If there are folks out there who can’t pay, they can always go to a traffic commissioner and talk about that.

“You can fine the person, but at some point, if those (fines) don’t work, you have to look at jail time.”

All five of Brown’s elected judicial colleagues either didn’t return requests for comment or deferred comment to the chief judge.

Municipal Court Administrator Dana Hlavac, too, demurred to Brown’s opinion on court-related matters.

USING RESIDENTS AS ATMS

More than 18,000 people were arrested for nonviolent, nonmoving violations in Las Vegas in 2014, according to jail records. A handful found themselves in handcuffs for offenses as minor as littering or spitting on the sidewalk.

Of the 134 low-level offenders sentenced to jail last year by Municipal Court judges, nearly 30 percent were put behind bars for nothing more than a fix-it ticket or moving violation.

Between all those sentencings, city judges might not have a lot of time to hear from each and every one of the city’s jailed traffic court defendants within 72 hours, as required under federal law.

But attorneys say they need to find the time. They say the court — which often requires in-custody defendants to make a first, televised appearance in front of a traffic commissioner, not an elected judge — is prolonging jail stays and violating constitutional due-process rights.

Traffic commissioners asked to preside over those appearances sometimes do little more than reschedule defendants for the next available slot on the court’s criminal calendar, effectively extending their stint behind bars.

Las Vegas defense attorney Dayvid Figler, who is a former traffic commissioner, said the system accomplishes two goals for the court: it eases elected judges’ caseloads and acts as a “very efficient shakedown system” aimed at indigent defendants.

“The idea is, we put the fear of God in them, then maybe they’ll come up with some cash,” Figler said. “There’s no one from Summerlin on that video (screen).”

Figler’s criticisms are far from the only ones leveled at the court over the past few months.

City employees say court marshals have unconstitutionally manipulated warrants to pre-empt judicial orders and dangle the specter of jail time in front of defendants being served with a warrant.

Municipal Court officials said they had no evidence that the court bars or discourages the practice, which was approved under limited circumstances in memos from 2008 and 2010 obtained by the Review-Journal. Chief Judge Brown said he wasn’t aware of the alleged warrant manipulation problems but promised to look into it.

Las Vegas staffers have likened the practice to coercion — the equivalent of treating the city’s most vulnerable residents like ATMs.

MORE MONEY, FEWER CASES

Area bail bondsmen compared Las Vegas court collection policies to similar policies in Ferguson, Mo., where weeks of rioting and grand jury proceedings followed the shooting death of 18-year-old Michael Brown, an African-American, at the hands of a white police officer in August. The officer, Darren Wilson, has not faced criminal charges in connection with that death.

The bondsmen called the traffic court a “collection agency” determined to preserve its right to threaten defendants with arrest for the most minor of offenses.

Las Vegas court officials dispute the characterization, explaining they do not “force people to pay money they can’t pay just so we can keep running our business.”

Forced or not, the court has found ways to squeeze more money out of fewer cases.

Per-case revenue is up 124 percent since fiscal year 2003, despite a 36 percent drop in the number of cases filed.

That’s thanks in part to several fine and fee increases enacted over the past decade, including some changes that could see defendants spend months or years paying the court hundreds or thousands of dollars in late fees before even starting to pay down an initial past-due fine. Per-case fee waivers awarded to those on a payment plan are now at a six-year low.

“The court’s policy is shake (defendants) enough, and money will come out,” Las Vegas defense attorney Caitlyn McAmis said. “It’s appalling, what they’re doing to these people.”

Nevada Supreme Court Chief Justice James Hardesty, an outspoken critic of fee-funded court systems, said some court revenue streams can create the appearance, if not the reality, of impropriety. He would prefer to see Nevada fund its courts through general fund dollars rather than rely on defendant-generated cash receipts often paid by poor, minority residents.

Hardesty also came out in favor of decriminalizing traffic offenses — the very move Las Vegas court officials rallied against in April.

“The limited jurisdiction judges of this state have repeatedly opposed (raising) administrative fees because this has become an alternate method of raising funds, without raising taxes,” Hardesty said. “I do think traffic offenses ought to be decriminalized, but as long as there is a fiscal consequence, changing that system might be difficult.”

Judge Brown said he, too, would like to see his court’s operations supported by state or city general fund dollars. He stopped short of taking a position on decriminalizing traffic offenses.

‘PROFIT AND GAIN’

Las Vegas has become creative to keep court revenue flowing in recent years.

At one point, the city even pulled jail staffers off their posts to help collect warrant fee dollars.

A handful of marshals who oversee inmates housed at the city jail once helped the Municipal Court bring in more than $2 million through the city’s “warrant program” — a 2011 initiative aimed at capturing some of the estimated $77 million in uncollected fines tied to Las Vegas’ thousands of outstanding misdemeanor warrants. The program, first enacted to avert dozens of threatened marshals’ office layoffs, was shuttered in 2013.

A Review-Journal analysis of publicly available data on almost 94,000 of those warrants says a lot about minor criminals whom marshals haven’t managed to hunt down over the years. That data suggests most of these offenders likely couldn’t afford to pay the court’s ever-rising fines in the first place.

It shows residents living in Las Vegas’ seven poorest areas accounted for almost three-fourths of those with unpaid warrant fines since 1991.

Defendants living in the city’s seven richest areas accounted for about 6 percent of traffic court scofflaws sought by the court over the same time period. A Review-Journal records analysis conducted in January found similar big gaps between the number of parking tickets written in the city’s richest and poorest neighborhoods.

Such efforts came as little surprise to lawyers who have spent time at the court.

“They’re not waiving fees like they were. They’re not giving people the benefit of the doubt like they used to,” said longtime Las Vegas traffic ticket lawyer Joe Maridon. “Across the valley, they’re trying to find ways to get more revenue.”

Nor did they shock court defendants.

“(The court) wants to grab that money so bad it’s unbelievable,” said Kim Blandino, a former jailhouse lawyer fighting a 2013 reckless driving conviction. “It’s not a body politic anymore. It’s there for profit and gain, basically.

“They’re so interested in the money they’re just violating every due process protection you’re supposed to have out there.”

There is nothing preventing city judges from making changes that would help the court avert future Ferguson comparisons or silence criticism similar to Blandino’s.

Nothing, perhaps, except their own livelihood.

City Manager Betsy Fretwell — who oversees a budget that includes $23 million collected from the courts last year — said court revenue actually has been flagging over the past two years.

Fretwell noted the city would have no choice but to prop up the court if, for some reason, it no longer could pay for itself.

She seemed to doubt that would ever happen.

“They’re one of the few municipal courts that cover most of their direct costs,” Fretwell said. “Do we keep a close eye on (the court’s) revenue? Absolutely. We watch every bit of revenue that comes through this place.

“After being through that recession, we have to. We’d be irresponsible if we didn’t.”

Contact James DeHaven at jdehaven@reviewjournal.com or 702-477-3839. Find him on Twitter: @JamesDeHaven

SMALL CRIMES,

HIGH PRICES

Maximum fines associated with the Las Vegas Municipal Court’s five priciest traffic violations, listed below, can run into four figures. Top-tier fines charged for these offenses — some of the most common committed by thousands of defendants enrolled in a court payment plan — total nearly $450 more than the typical fine paid in traffic court.

$1,135

No proof of insurance

$1,135

No insurance/security

$655

No driver’s license

$655

No driver’s license in possession

$655

Improper driver classification on driver’s license

Source: City of Las Vegas standardized fine and bail schedule, effective Feb. 13, 2013.