Lake Mead will only receive a fraction of this year’s snowpack. Here’s why

Every year, when snow from the Rocky Mountains melts into water, it finds its way into Lake Powell, the country’s second-biggest reservoir. But with each passing season, less snowmelt becomes reservoir water that 40 million people can use to drink, plant crops or satiate their lawns.

Runoff into Lake Powell has a direct tie to how much water can be sent downstream to Lake Mead, from which Southern Nevada sources roughly 90 percent of its water.

“Warming puts an additional demand on the system,” said Russ Schumacher, Colorado’s state climatologist and a professor at Colorado State University. “The thirstier the air is for water, you’re going to lose more of that water to that thirst.”

Atmospheric demand from climate change is one piece of the puzzle, as Schumacher puts it, as to why federal projections show that runoff into Lake Powell will reach about 67 percent of a historic average this season. Other reasons include dry soils and hotter temperatures accelerating sublimation, the process where solid snow turns only into gas instead of liquid, Schumacher said.

Snowpack itself above the reservoir has hovered between around 84 and 91 percent of average in this month’s readings — another poor showing that continues over two decades of Western drought.

“It’s not looking like it’s going to be a good year for water on the Colorado River,” Schumacher said. “From a water perspective, it’s been a lot of years of not good news. That bad news is going to continue this spring and summer.”

The trend of less available water in Western reservoirs is underscored by ongoing, tense negotiations between all seven states in the basin. The Lower Basin states of California, Nevada and Arizona continue to disagree with the Upper Basin states of Colorado, Utah, Wyoming and New Mexico on a path forward before the river’s operating guidelines expire in 2027.

Dry soils, sparse rains

However below average snowpack has been in the Rocky Mountains, the Lower Colorado River region has had it much worse, spurring concerns for smaller reservoirs, groundwater and the rural water users who rely on them.

Most snow stations collected samples in Arizona and New Mexico showing less than 30 percent of average this month. A drought update from federal forecasters in early March even carried the title “Abysmal Snowpack Defines Winter for Arizona and New Mexico.”

That bad luck extended to Southern Nevada’s Spring Mountains this season, where it took months for any measurable snow to fall at all. Snowpack there is critical for regions of southwestern Nevada and the Death Valley area, where communities can only access drinking water through personal groundwater wells.

Dan McEvoy, of the Western Regional Climate Center at the Desert Research Institute, said the numbers could spell trouble, especially considering current trends of less snowpack each year.

“For rural communities, that is their water supply,” McEvoy said.

Northern Nevada, on the other hand, has had a significantly wet year in terms of snowpack. From the watersheds of the Owyhee River to the Humboldt River, numbers have easily stayed near or above 120 percent of average.

Fire risk connected to snow

But the overall basin’s snow drought presents something even more challenging — wildfire risk.

McEvoy warned of how the lack of rain in some basin states, coupled with meager snow that melts earlier, could dry out soils.

The latest Western drought update from the federal government warns that projected, warmer-than-normal spring temperatures won’t do Nevada or California any favors when it comes to wildfire.

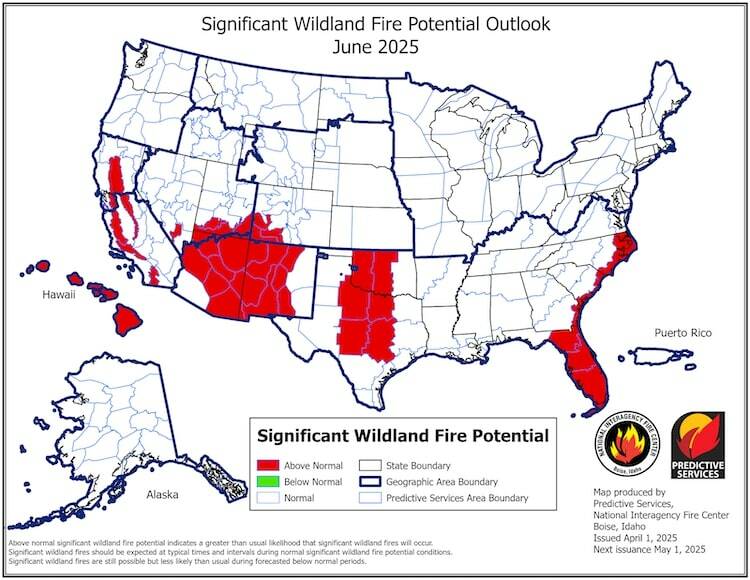

A map shows one region of Southern Nevada, northwest of Las Vegas, with above-normal wildfire potential in June. Nearly all of Arizona and New Mexico are marked with increased chances, too.

Fire forecasters are working to better understand and forecast the connection between snow drought in the West and wildfire, McEvoy said.

“Especially during the really dry season, in May and June before the monsoon starts, I think that’s when eyes are going to be on the fire season,” he said.

Contact Alan Halaly at ahalaly@reviewjournal.com. Follow @AlanHalaly on X.