Empire: The death of a Nevada company town

EMPIRE -- When it comes to the hardship, heartache and havoc created by the housing collapse, the only difference between giant Las Vegas and this tiny town is this: Next Tuesday, Las Vegas will still exist.

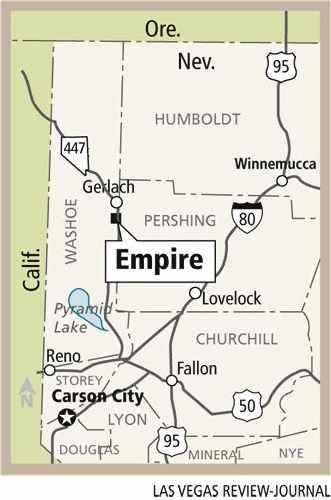

Empire, about 100 miles northeast of Reno in the Black Rock Desert, will become an instant ghost town, its gypsum mine vacant and drywall plant shuttered for the first time since 1923.

Even its ZIP code, 89405, has been wiped from the map, a final insult to one of the last true company towns in America.

No bureaucratic process, however, can erase memories made there or at Gerlach, the other wide spot in the road five miles north on Highway 447 in Washoe County.

They are inextricably intertwined, an inescapable inevitability in the vast American outback that is rural Nevada.

DEATH OF AN EMPIRE

Jan. 31 was the last workday for 95 of the 99 U.S. Gypsum employees at the mine and plant. They turned gypsum into sheetrock, a trademarked name and the most common wallboard used in the construction industry.

Four workers remain. Two will be gone by month's end while the other pair keep their jobs through December. Workers with families were allowed to stay for free in company-provided housing for another five months so their children could finish the school year.

"It was business," engineering manager Mike Christopher says of the shutdown. "There was nothing personal. We all hated to see it close. This is a terrible thing, but we closed because nobody was showing up and picking up sheetrock."

Rumors have been a distraction. For the record, he says, Chinese drywall manufacturers have not cornered the U.S. market.

"This is about the foreclosure crisis," Christopher says. "There are a ton of nice empty homes that people can buy at a good price. Nobody is building."

For the 15 years leading up to the burst bubble, the Empire plant cranked out sheetrock around the clock. "We went nonstop," he recalls.

Building slowed in 2006 and by 2008 orders had shriveled to a fraction of prior years. Still, the plant limped along until the inevitable decision late last year.

ONE OF THE LAST 'COMPANY TOWNS'

The "town" of Empire is a bit of a misnomer.

Empire is more like a subdivision, albeit one where all the homes were owned by the mine and employees rented them at bargain basement rates -- $125 a month for an apartment; $250 for a two-bedroom home.

A lazy walk around town might last 20 minutes -- if you take your sweet time.

A modest nine-hole golf course meanders through the streets and churches and community center, and was a popular perk. The community's four streets are lined with the trees of Northern Nevada -- poplar, cottonwood, pine and elm. For the moment everything is still green, but summer's heat is right around the corner and it won't take too much arid neglect before Mother Nature takes back what is hers.

The state of front yards makes it easy to spot who has left and who remains.

The empty homes already appear decrepit. Their lawns, though still green thanks to a wet spring, are overgrown. Weeds have sprouted and bushes go ungroomed.

Satellite dishes on metal roofs stand like pilfered garden gnomes. Somehow they seem painfully alone, like a loyal family dog sitting and staring sadly at the door, waiting in silent desperation for its owners to come home.

Other yards are fresh-mowed despite the certainties they will soon leave forever.

Those who still live here continue to maintain their routines.

They are not in denial, not rearranging the deck chairs while the Titanic sinks. They are for the most part humble people who live to hunt in the mountains and fish in the lakes and ponds that dot the nearby landscape.

"This isn't the middle of nowhere, but you can see it from here," is a popular local saying.

That's the sad thing. They want to stay here, but most can't.

The news could be worse. Most anyone who wanted to found a job at one or another of the region's gold mines. But even though the pay is higher, so too are rent, gas and home energy costs.

Gold has been able to defy the economic downturn's ravages because the precious metal is considered a hedge against weak currencies and an unstable economy. But gypsum is not gold, and so this particular Empire, barring a swift and sure economic recovery, will not strike back.

CAUSE AND EFFECT

Five miles down the road in Gerlach, where Empire's children were bused to school each morning, 23 employees of the Washoe County School District anxiously await news.

Ten of those 23 are teachers, and while a couple retired to stay here, the rest were guaranteed a spot in one of Reno's schools.

Nerves are frazzled. Reassignment was supposed to happen last month but as of Wednesday nobody had heard a thing.

Last week, the adults set aside their anxiety but not their emotions. Tuesday was the last day most of the people who learn there or teach there will ever spend there.

That morning, under a blue Nevada sky, the students of E.M. Johnson Elementary School -- all two dozen of them representing five grades -- gathered around the flagpole and earnestly pledged allegiance to the flag.

Then, in almost perfect harmony, as they have every school morning this month, they sang "It's a Small World."

Come September's school opening, there won't be enough of them to circle the flagpole.

The world really is small here in the Black Rock Desert, best known to outsiders as home to the annual Burning Man Festival, a counterculture extravaganza. Gerlach, a town that defines quirky, plays host.

"Not no, but hell no," says one miner when asked if he ever drove up the road a few miles to see what all the fuss was about. Another, though, says the artwork displayed is phenomenal to see, "once you get past the dope and the nudity."

The land speed record was set near here and the great outdoors draws hundreds, but on most days life slows to school zone speed.

Consider the 2000 U.S. Census, which found that Gerlach and Empire were home to 5.3 people per square mile. The population density of Las Vegas? More than 4,200 people per square mile.

For both students and teachers, the world is about to get much bigger. For many of the kids, to paraphrase a 1987 REM song title, it's the end of the world as they know it.

"We worry for them," Principal Edna LaMarca says.

At first, it's unclear if her concern is for teachers or their students. Turns out she has worries for both.

She laments the inevitable loss of critical individual attention students got in smaller classes. Maybe the class had only 10 students, but they represented four grades.

The numbers seem to back her up. For years, Gerlach has graduated all its seniors, and no student has ever failed to pass state proficiency exams.

And teachers in Gerlach might be more versatile than are their big city counterparts. The science teacher also teaches welding. Others teach honors classes for the gifted and remedial classes for those lagging behind -- at the same time.

They teach history with a passion and math with patience.

LaMarca worries they might find difficulty adjusting to 40-student classrooms in Reno, but she also has faith they will adapt. "I think they'll surprise me. They'll surprise themselves. They are smart people and dedicated."

Heather Neil, who has taught high school English and Spanish at Gerlach for 14 years, is confident: "I'll just break the class into smaller groups."

She met her husband Bill, an elementary teacher, on Teachers Row, a collection of trailers where faculty live, at least until Aug. 1 -- the deadline they have to vacate the premises.

They had hoped to raise their three children in Gerlach and watch them graduate from Gerlach High.

But future graduations will be few and far between.

THE LAST GRADUATES?

Currently, no seniors have enrolled for next year and the three remaining high school students have opted to take courses online.

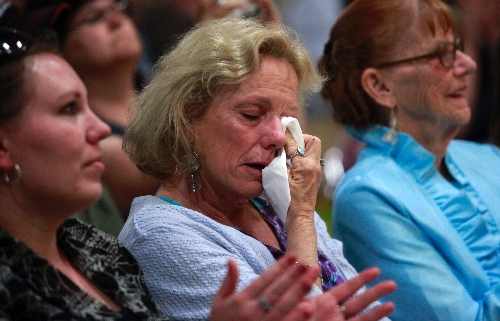

That made Tuesday's Gerlach High graduation ceremony even more emotional than usual.

The 10 seniors, six boys and four girls, were the largest senior class in a decade. They are a closely knit group -- almost half of the class is dating.

Raven Lester moved to Gerlach in third grade and hated it with all the passion a third grader can muster.

"It didn't even have a McDonalds," class salutatorian Lester recalled in a tearful farewell speech. "What are you supposed to think when there are more bars than places to shop?"

She says that she grew to love her classmates, her teachers, and a town "so small that everyone knows your first name, your last name and all your business."

Classmate Anthony Gary Marks echoed her feelings, delivering a brief but powerful speech on redemption.

Marks was a dropout and living in California when his grandfather summoned him to Gerlach to work in his store during the insanity that is Burning Man.

But when the festival ended, he called his mom and told her of his plans to stay. And to go back to school.

His transcripts were a mess and he was woefully behind, but Marks worked hours and hours to catch up. "I just want to thank all of you for being accepting," Marks told the roughly 220 attendees at his graduation.

Women wiped their eyes dry while men chewed on their bottom lips.

Folks here are proud of more than just the sheetrock they have produced. Engineering manager Christopher's two sons spent their school life at Gerlach, and the seemingly far-away events of 9/11 had a profound impact on both. One joined the Marine Corps, which sent him to Officer Candidate School and then to flight school. Today he flies F-18 fighter jets.

The younger brother surprised his parents even more.

"He told us one day he was scheduling interviews with senators about going to one of the service academies," Christopher recalls. "We had no idea. I wasn't in the military. Our parents were in World War II, but we're not a military family."

They are now. The younger Christopher brother went to West Point and just earned his Green Beret.

He leads Special Forces ops in Afghanistan. "I don't know what he does. He can't tell me. He just says, 'Dad, I'm fine. We're doing Secret Squirrel stuff up here you don't need to worry about.' "

THE INCREDIBLE SHRINKING SCHOOL

Even before the mine closed, Gerlach High was small. Unable to field even an eight-man football team, played by Nevada's smallest schools, Gerlach held its Homecoming Week during basketball season.

This year, without enough girls to field a team, they were allowed to try out for the boys' team.

Homecoming queen Chelsea Newman and valedictorian Myriah Brittany Collette Keesee were starters. And all of the girls made the team.

"Nobody gets cut here," LaMarca says. "We need every warm body we can get."

And that's the problem.

The school year began with 80 students, ranging from three adorable pre-schoolers to the 10 seniors who graduated Tuesday.

That number dropped significantly to 51 right after the mine closed.

It looks like next year's student body will consist of roughly 12; one for each grade on average, and most of them from ranch families.

In some cases, the district transports "ranch kids" 40 miles up and down a dirt road in an SUV. A bus is neither necessary nor practical: Northern Nevada winters require a nimble four-wheel drive, not a big yellow bus.

THE QUIRKIEST TOWN IN NEVADA

There were two churches in Empire -- two more than in Gerlach -- but Gerlach boasts the area's three bars.

The Miners' Club was built in 1935. Current owner Bev Osborn and her late husband bought the bar in 1969, the same year her 21-year-old son was killed in action in Vietnam.

She first arrived in the area in 1947, just out of high school, but left for Las Vegas where she worked for the phone company in the 1950s and '60s. The last half of her eight-plus decades has been behind the bar at the Miner's Club.

From the outside the bar looks its age, 75, and six-and-a-half decades of tobacco smoke and spilled beer, blood from the fights the "railroad guys" started and too much cheap perfume have permeated its inside.

On the walls are photos of a British company's jet-powered car that in 1997 broke the sound barrier on land -- the desert floor outside of Gerlach.

The healing hands of time have dimmed her memories of son Randy's death in battle all those years ago. But Osborn doesn't hesitate when she recites the speed that driver Andy Green, at the time a pilot in the Royal Air Force, was traveling when he literally became the fastest thing on wheels: 764.168 she says, jabbing a right index finger with each numeral.

She opens daily at 5 p.m., but might close if she doesn't have a customer by 5:15. Like most Gerlach businesses, the hours are flexible.

The area's one cafe opens promptly at 6 each morning, but plan a late dinner at your own peril. The only place to get a hot meal for 80 miles in any direction closed last week at 9 Sunday night, 6:30 p.m. on Monday, and about 8:05 p.m. Tuesday.

And just try to sit in the last seat on the right at the lunch counter, next to the ice cream case.

"Get up," the waiter scolds. "That's Bruno's chair."

Even if it were the only empty seat, a visitor is assured in no uncertain terms that the seat is reserved for Bruno Selmi, an Italian immigrant who Osborn -- his competitor in the hyper competitive Gerlach bar scene -- says earned his status.

"He worked really hard to get what he's got," Osborn says.

What he's got is the only cafe, the only motel -- ambitiously called Bruno's Country Club -- and the only gas station. Last week, regular unleaded there went for $4.82 a gallon.

Osborn, 85, showcases an eternal optimism and accents it with a well-honed wit.

"I'm so lonely," she says, breaking every heart in the room before delivering the punch line. "But I'm not ready for a relationship yet."

Various townspeople step in and check on her, she says, and she has no plans to leave: "I had several people ask to buy the bar, but I didn't let it go. Now, who in their right mind would buy it? The mine's closed."

'THIS IS WHERE WE BELONG'

Steve and Judy Conley perhaps best define the death of Empire and the dramatic downsize of the school.

Steve marked his 40th anniversary at the U.S. Gypsum operation on the day he was let go.

Judy has been a secretary at Gerlach schools for 37 years.

Like his father before him, Steve managed the quarry. He spent his life at the mine after graduating from Gerlach High in 1970. His mother graduated a Gerlach Lion in 1948.

And while many people describe what the shutdown means to them and the town, Judy is uniquely succinct.

"I've lost all my friends. All of them," she laments, tears ready to fall again. "We raised our kids together. We lived our lives together. I'm going to miss them so much."

The Conleys are staying. So are the Christophers, who have a small horse ranch in the area.

"I love it here," Mike Christopher says. "I'm going to miss the social aspects, but this is where we live.

"This is where we belong."

Contact Doug McMurdo at dmcmurdo@reviewjournal.com or 702-224-5512.