Federal protection for Amargosa River may boost tourism in region

The Amargosa is less a river than the suggestion of one.

For much of its run from the Nevada high desert to the bottom of Death Valley, it is a dry ribbon under sun-bleached sky.

Unless you arrive in the middle of a flood, you can easily walk across it without getting your socks wet.

But there is one place where the river flows year round.

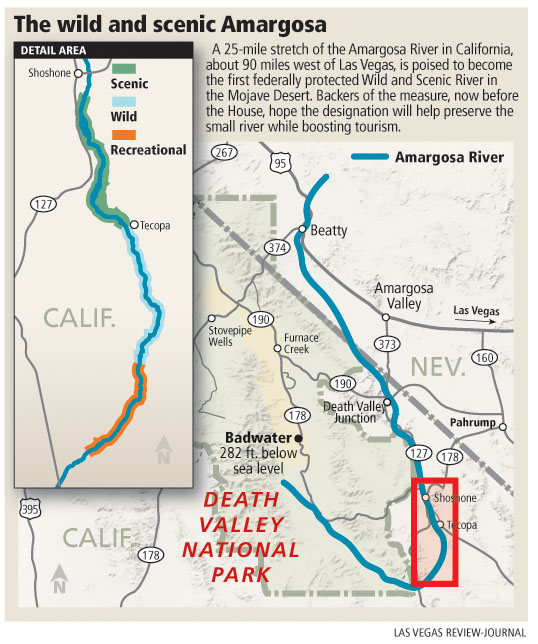

Starting in the tiny town of Shoshone, Calif., 95 miles west of Las Vegas, the river rises to the surface and runs above ground for more than 25 miles, feeding narrow bands of green in a bone-colored landscape.

It is here that an act of Congress soon could establish the first -- and perhaps only -- section of Wild and Scenic River in the Mojave Desert.

Backers of the measure are counting on the designation to bring new protections and a boost in tourism to the sparsely populated area at the eastern edge of Death Valley National Park.

"We're hopeful it's going to happen any day," said Brian Brown, owner of the China Ranch Date Farm, about 15 miles south of Shoshone.

The Wild and Scenic River designation has been bundled into the Omnibus Public Land Management Act of 2009, a massive federal lands bill that is expected to come to a vote in the House later this month.

The bill received Senate approval on Jan. 15.

If the measure is passed into law, a 12-mile section of the river from Shoshone to Tecopa, Calif., would be classified as scenic. The next eight miles, as the river descends through the barren and roadless Amargosa Canyon, would be classified as wild. And the five miles of river south of there would be classified as recreational, preserving access by off-roaders from nearby Dumont Dunes.

A scenic classification for a river usually limits development of road crossings and riverside structures, but depending on existing uses, it may or may not prohibit motorized vehicle access.

Wild classification is more restrictive and generally bars motorized access, road construction and other development.

In the case of the Amargosa, the section set aside as wild is already part of a wilderness area in which motor vehicles are prohibited.

Though some concerns have been voiced upstream about the impact the river's designation could have on water development in Nevada, Brown said the protections are reasonable, apply only to federal land within the listed sections and generally reflect how the land is being used now.

"It's a good compromise," he said. "Down here I haven't met anyone who doesn't think it's a good idea."

It has been a long time coming, too. Just ask Steve Evans, conservation director for Friends of the River, an organization dedicated to conserving California's rivers.

Evans said advocates for protecting the Amargosa first started talking to the federal Bureau of Land Management about the river in 1998.

After a study of the area, bureau officials in 2002 agreed that the river qualified for Wild and Scenic status.

On maps at least, the Amargosa River springs to life in Nevada's Oasis Valley, where it slopes away from Yucca Mountain and the Nevada Test Site.

One Nevada water official described it as "a dry wash," but the river does surface for a bit as it winds through Beatty. After that, it runs dry for much of the next 75 miles to Shoshone, where it collects runoff from the first several dozen of seeps and springs it will meet along the way.

South of Dumont Dunes the river makes a hard right turn, cuts under California Route 127 and curls back to the north, where it empties into the broad and briny sump known as Badwater.

It is the farthest downhill that water can flow: 282 feet below sea level, the lowest point in the Western Hemisphere.

Las Vegas conservationist John Hiatt said the Amargosa River is especially important because it supports critical habitat in a landscape that otherwise tends to support very little of anything. "Anytime you have water in the desert you have an area that is very attractive to wildlife," he said.

Among endangered birds known to frequent the area are the Southwest willow flycatcher, the yellow-billed cuckoo and the least Bell's vireo.

Some of the area's rarest residents -- aside from people -- are tiny fish species that scratch out their existence in isolated, spring-fed streams and pools. Brown calls them Ice Age remnants. "They're fish who survived the last big dry-up, and they're still here."

Federal designation is not expected to bring sweeping changes to the river. There are no plans for a visitor center or any other major facilities.

What Brown and others really want is a regular line item for the Amargosa in the BLM's budget, so the agency can begin to act on long-standing plans for the area.

The BLM completed a management plan for the Amargosa River about five years ago, but there has been "no money or resources to implement it," said Brown, whose roots in the area go back to 1903.

Advocates for the Amargosa hope that with some minimal funding, the BLM could work to halt erosion and the destructive spread of non-native tamarisk plants in the Amargosa Canyon. They also hope to see improved hiking and biking trails and a few picnic tables, information kiosks and interpretive signs -- anything to attract more visitors to an area now largely dependent on tourism.

"That's about all we have to offer. The mining is all gone. It's either this or starve," said Brown, who has operated his spring-irrigated date farm at the edge of the canyon since 1979.

"I hope to get an increase in business, quite frankly. And I think it will be good for the whole area."

Contact reporter Henry Brean at hbrean@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0350.

Audio slideshow