Hard work and worries dog a Nevada ranch family

It’s not just Nevada’s 150th birthday in 2014.

The Fallini family also got its start in the Silver State in 1864, when Italian immigrant Giovanni Fallini settled in Nye County.

Fallini dabbled in mining for a bit, but by 1868 he was ranching near the Reveille Range outside Rachel.

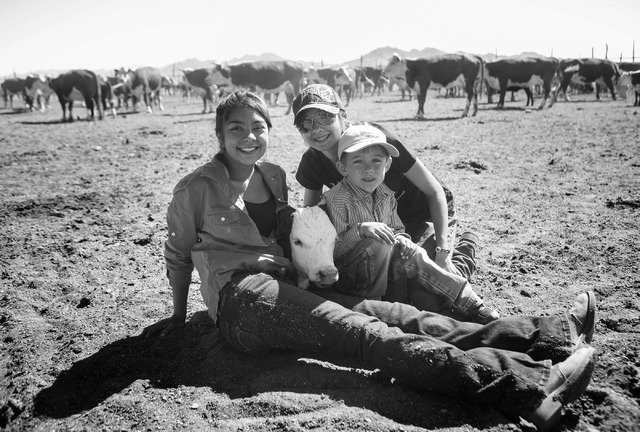

Five generations later, Fallini’s great-great-grandson, 6-year-old Giovanni Berg, follows his parents, grandparents, sister, aunt and cousins onto the range as the family works Twin Springs Ranch, running 1,800 head of Hereford beef cattle across two arid valleys in spartan central Nevada.

At 663,000 acres, or more than 1,000 square miles, Twin Springs covers more than three times the acreage of Red Rock Canyon National Conservation Area, and nearly 10 times the area of the city of Las Vegas.

But even as the family has sustained a thriving ranch under some of the toughest conditions in the country, its grip on the land has never been more tenuous. Giovanni Berg may never take the reins of the ranch his ancestors started in the state’s first days. The family blames a federal agency and courts that put legal minutiae over century-old law. Between the two, more than half of the ranch’s profit in 2014 will go to legal costs, an added expense in already difficult times for Nevada ranches.

“There’s no guarantee in this business, not just from decade-to-decade, but even year-to-year,” said Anna Fallini, Berg’s mother. “With the fragility of our operation, you have no idea how long you’ll be here.”

If ranches such as Twin Springs die, they’ll take a big part of the state with them. The industry isn’t huge in Clark County, but elsewhere it keeps rural communities alive. Ranching posted $441 million in cash sales statewide in 2012, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. And the ranches are vital to protecting Nevada’s environment.

To get a look at what Nevada has to lose, the Review-Journal visited Twin Springs during branding season in early June.

LONG HARD DAYS

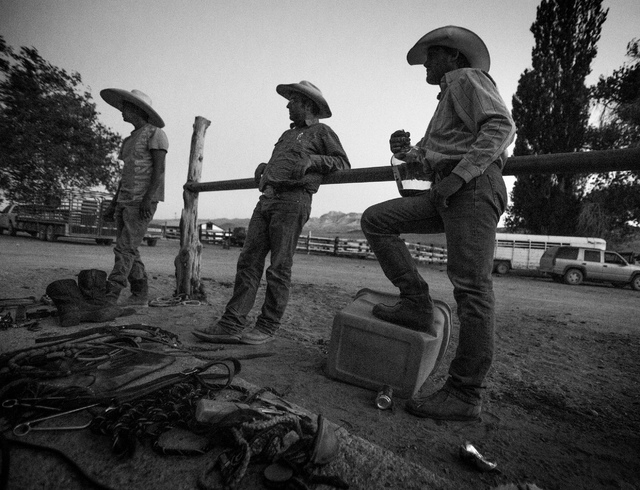

It’s 3:45 a.m., and Anna Fallini’s alarm clock is buzzing. She gets up to make breakfast for the cowboys staying in the bunkhouse for branding season. As the cowboys feed and water their horses, Anna lays out a breakfast of bacon, eggs, lemon-poppyseed muffins and fried calves’ testicles fresh from the previous day’s branding. Fallini’s husband, Ty Berg, is already out, preparing for the day ahead.

By 6 a.m., the cowboys are on their way to one of 26 ranch corrals to begin branding calves collected there.

Meanwhile, Anna’s father, Joe Fallini, takes off in his helicopter to drive more cattle to another corral a few miles south on state Route 375. Anna’s sister, Corrina, and their mother, Sue, use pickups to drive cattle toward the corral, staying in constant radio contact with Joe. It’s a chaotic, bone-rattling, teeth-chattering ride: Corrina charges across the countryside like a Hollywood stunt driver, grinding gears in an old Ford, bouncing across ditches, honking and pounding her door to encourage cows to “make the right decision” and head toward the pen.

Corrina, an elementary school teacher in Carson City during the school year, doesn’t let a single cow escape. The roundup takes less than an hour — helicopters and trucks are much faster than horses.

By 9 a.m., the cowboys arrive at the second corral and set to work. A half-dozen cowboys and cowgirls spend an hour culling cattle the ranch will keep, mostly calves and fertile heifers, from those headed to market in Twin Falls, Idaho.

Then branding begins.

Working in teams of three or four, the ranch hands lasso 200-pound calves and wrestle them to the ground. They cut ears and shoulder wattles, give supplements and vaccines, castrate and brand each animal — all in about a minute per calf.

It’s grueling work in 90-degree heat, through a nonstop scrum of charging livestock and a constant dust cloud that’s flattened more than one cowboy with pneumonia. Everyone gets involved, from the 14-year-old cousins who inject vaccines, to the Fallini sisters, who castrate and brand, to Berg, who ropes calves. Days are filled with long hours on horseback, tending white-hot fires to heat branding irons and loading cows into trailers bound for market.

Over three weeks with no breaks, they’ll brand 1,300 calves.

There’s a half-hour break for lunch, but the work day goes until dusk. Only Anna peels off a little early to make dinner. Afterward, she cleans dishes and handles the day’s paperwork. She’s in bed around 10, her alarm once again set for 3:45 a.m. The compact woman who runs in Las Vegas’ Tough Mudder obstacle-course race never looks tired or stops smiling.

Twin Springs has survived for generations through adaptation. The ranch seamlessly combines old and new. Ty and Anna live on the ranch with their children in a 100-year-old house moved in from Liberty in 1947. Cattle raised here are direct descendants of those brought to the range in 1900, and they bear seven different brands the family developed over the generations.

But the family also hires cowboys with Facebook posts made possible by Wi-Fi Internet access. The children take selfies with day-old calves. The biggest recent crisis involved Giovanni Berg accidentally deleting his favorite Dropkick Murphys song from his mom’s iPhone.

But adaptation stretches only so far, and the Fallinis say the operation’s future is being tested by the U.S. Bureau of Land Management’s evolving mission, as well as a multimillion-dollar negligent-death lawsuit against the ranch.

Back in the 1930s, the BLM allotted grazing rights to settle brutal range wars between ranchers using federal land.

Today, there’s a different mission for the agency, which manages federal land that makes up 657,520 acres of Twin Springs, where the Fallinis own all of the water rights.

The BLM now focuses on preserving the range for multiple uses, including recreation, wildlife conservation, renewable energy, mining and, yes, ranching and livestock, said Erica Szlosek, communications chief for BLM Nevada.

In that delicate dance, toes get stepped on, Szlosek acknowledged.

Twin Springs has filed 31 lawsuits — winning 30, Anna said — over eight decades to fight what the family calls the agency’s whims.

“We can survive drought. We can survive bad weather. We can survive disease. What will ultimately be the end of our operation, as it has been for so many ranchers, is the BLM and their practices,” Anna said.

The biggest issue by far? Wild horses.

The ranch can accommodate 170 wild horses, but in the 1980s and early 1990s the property’s wild horse population soared to 2,300 as public sentiment turned against culling the herds by sending some horses to slaughter. The horses overran Twin Springs’ cattle in the fight for water and food. The ranch had to pump water around the clock to keep its animals alive, Joe recalled.

It took a decade and multiple court orders to get the BLM to remove the horses, but the damage was done. Joe estimates that horse watering cost his family $1 million, and Twin Springs still hasn’t regained the two-year supply of forage it once held in reserve for drought years.

The BLM could also stop grazing on part of the ranch’s allotment at any time if it decides there’s a drought, Anna said. Such an order would devastate the operation, she said.

“It takes 130 years to build these ranches,” Joe said. “It takes one strike of a bureaucrat’s pen to wipe them out. I don’t know a single ranch that’s been made since (the BLM became active here), but I know a lot that have been put out of business.”

The BLM says it uses science-based drought environmental assessments to determine how many cattle to allow on federal land.

“If the drought is causing water resources to dry up, we don’t want to put cows out there,” said Tim Coward, manager of the BLM’s Tonopah field office.

Coward said he feels the BLM has cultivated a good working relationship with the Fallinis, and he respects their generations of experience on the land. He has spent time with the family explaining drought assessments. He said he plans to continue working with Twin Springs on the matter.

The Fallinis — who invite the public to visit their ranch and learn about their work — say the agency exaggerates the threat of drought.

Flint Wright, of the Nevada Department of Agriculture, agreed. He said central and Northern Nevada generally saw good rain this spring. There’s a “considerable amount of grass” setting up a “good to even excellent year, as far as grazing goes.” And rain-forming El Niño patterns over the Pacific Ocean are expected in fall and winter.

“There’s actually quite a bit of forage out there and available, so I would say they (the BLM) have overreached to a certain extent,” Wright said.

Statewide, the number of animal units per month grazing on the land has fallen to 450,000, its lowest level since the Great Depression, Wright said. In a normal year it’s more than 500,000 units per month. Some of the drop is curtailing due to the recent drought. But the Forest Service and the BLM have been limiting grazing since at least the 1970s, he said.

The BLM said that’s because it’s looking at a bigger picture.

“At the core of our mission is multiple use and sustained yield. That means sometimes making choices that people who are looking for very short-term benefits on the land don’t agree with,” Szlosek said. “Our mission is not economic in nature. We’re not a business. We don’t turn a profit. Our success is leaving the land in good shape for future generations. So the core of what we do sometimes puts us at odds with people who are looking to the land to make a living.”

That kind of talk rankles the Fallinis.

Why, they wonder, would anyone mistrust the ranch’s stewardship when the family has maintained grasslands and water resources for 150 years? Why, they ask, would the family abuse the land when all they want is to leave Twin Springs to their children and grandchildren? And if cattle are run off the range, who will be on the ground every day, watching the grasses and monitoring the water that nourishes antelope, elk and deer?

That environmental stewardship is especially important, Wright said.

“Ranching is basically the only landscape-level tool we have to manage invasive plant species in the state,” Wright said. “That benefits tourists in terms of recreational opportunities, and it helps wildlife populations.”

Without ranching, Nevada would lose a key check on wildfires, as the invasive cheat grass that cows eat in spring and fall would grow out of control. And the state would lose its most renewable economic resource. Mining and gambling wax and wane; people always need to eat, Wright said.

But in Twin Springs’ fight to keep feeding people, it faces a more immediate threat than any federal agency.

OTHER THREATS

In July 2005, California mining geologist Michael Adams was driving his Jeep Wrangler at night on state Route 375, through Twin Springs’ open range, when he hit a cow and was killed. His mother sued Sue Fallini, whose brand was on the cow, for $9.2 million, for neglecting to take “reasonable precautions” to prevent it from wandering.

Nevada law says no livestock owner “has the duty to keep the animal off any highway traversing or located in the open range, and no such person, firm or corporation is liable for damages to any property or for injury to any person caused by any collision between a motor vehicle and the animal occurring on such a highway.”

But that doesn’t prevent a lawsuit.

Unbeknownst to the family, their attorney failed to answer discovery demands or make court dates. Documents filed with the Nevada Supreme Court in 2011 note open-range laws gave Sue a “complete defense,” and that in June 2007 the lawyer told Sue the case was “over” — she had won.

Actually, the case was just beginning.

The court saw the lack of a response as an admission the range wasn’t open, and that Sue had failed to take proper precautions.

In 2009, Judge Robert Lane, of Nye County’s Fifth Judicial District Court, ordered Sue to pay Adams’ family about $2.7 million. Fallini appealed to the state Supreme Court, which sent the case back to Lane’s courtroom for reconsideration.

The family expects a decision any day now, but they’re not hopeful. They have backup plans in case the judgment causes the ranch to fold, but they say it’s painful to imagine a time when they can no longer work the land.

Contact reporter Jennifer Robison at jrobison@reviewjournal.com. Follow @J_Robison1 on Twitter.