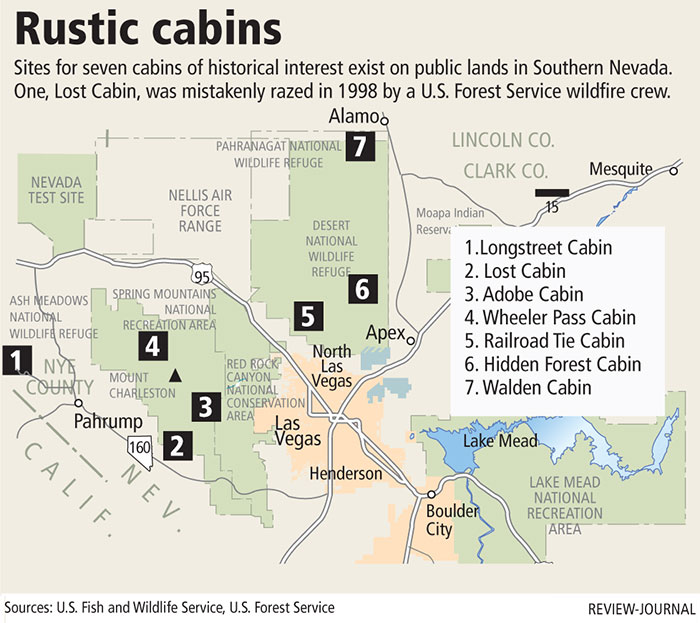

Historic Hidden Forest Cabin getting a facelift

Kent Olson flipped open his pocketknife and jabbed it into the bark of a log inside Hidden Forest Cabin. The blade stuck with ease.

"None of this lasts forever," he said, pulling the blade back out. "Pine doesn't do good getting soaking wet. Then you have the summer heat."

Olson, a mountain man from Husum, Wash., just north of the Oregon border, is the 68-year-old saw-slinger the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service sent last week to replace four rotting logs in the rare, century-old cabin and repair its leaking roof.

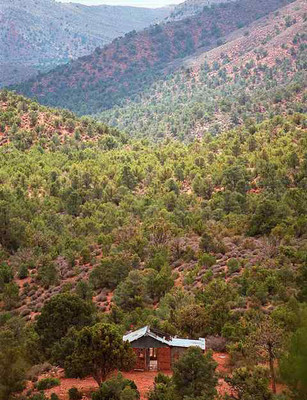

The cabin sits at about the 8,000-foot elevation of the Sheep Mountains in Desert National Wildlife Range, more than an hour's drive through the refuge over a bumpy, washboard road on the northwestern outskirts of the Las Vegas Valley.

Historians believe the cabin could have been built as long ago as the late 1880s or 1890s and used by hunters, trappers, prospectors and maybe outlaws in its early years.

It was standing in the 1920s at the beginning of Prohibition, when they think bootleggers lived in it to distill moonshine before the federal game range was established in 1936. A couple of other log structures flanked the cabin at one time.

Rusted fenders and engine remnants from what Olson said is a "1928 or 1929 Chevrolet" poke from the rocky soil a few dozen yards downhill of the cabin, evidence that vehicles could reach it 80 years ago, long before floods and landslides made the wash too treacherous for motorized travel that is now restricted.

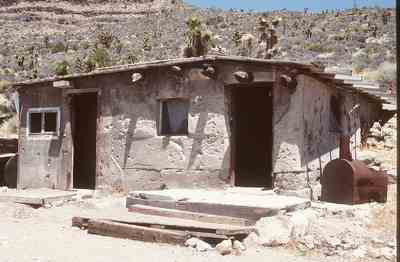

It's recognized by the government as an historic building. But Olson also calls it "a funny little house. It's wider than it is long."

"What's cool about this house is there is a lot of public use for it. It's nice to stay in the style it was built. ... The temptation is to make it better than it originally was."

Olson intends to complete the $30,000 restoration task this month with help from hiking groups and Boy Scouts who trek to the cabin.

He's relying, too, on his experience from years of working on historic Wildlife Service structures and knowledge handed down from his Swedish ancestors.

"My dad bought me an axe when I was 6 years old," he said, explaining how he wasted no time chopping down the family clothes line pole.

"My grandfather was a great axe man for corners," Olson said. "And I've done a lot of axe work and chopping work. I do about four of these jobs a year."

With only a trace of sweat dampening his white beard, Olson had hiked to the cabin early Tuesday, striding ahead of his wife, Joy, and a team of archaeologists and volunteers.

Against the trunk of a 2-foot-thick Ponderosa pine, he parked ski poles he had used to navigate the 6-mile trail that follows a gravel wash up Dead Man's Canyon.

Upon arriving at the cabin he glanced at his watch. "A new record -- 2 hours, 15 minutes," he said.

Besides hauling an axe and a saw to the camp, he had strapped a custom-made banjo on his backpack. After carefully untying it from his pack, he sat down at a picnic table and briefly plucked the strings one at a time.

"It's going to take me an hour to tune this thing," Olson said.

But it wasn't long before he was playing chords and a bluegrass melody, a short entertainment break before getting to the task at hand.

A few steps from the picnic tables, the cabin's rustic, hinged door stood partially open with its baseboard jammed against the cabin's floor, scraping it.

"I really like this door. It's old," he said. "It has this trim that's mitered the old-fashioned way."

But the floor "was put in after the cabin was built."

There was just enough time to assess the workload before a helicopter thundered over the normally quiet forest.

A 150-foot-long cable dangled with the first of several cargo loads of "shiplap" roof boards, rafter poles and "purlins" -- horizontal roof supports -- that he had milled from fallen Douglas fir trees in Washington.

The wood, and corrugated tin from Finley National Wildlife Refuge in Oregon, had been trucked to the helicopter's staging area at the trailhead.

On the first drop, one board fell from the bundle high above the trees and fluttered like a Popsicle stick caught in a whirlwind as it descended to the forest floor and broke apart. Olson rushed to retrieve it but was glad to see that the rest of the boards made it safely to the drop zone.

Olson had visited the cabin last year to take measurements. He returned in April to cut logs from the forked trunk of a dead Ponderosa pine uphill of the cabin to match the rotting ones the team will replace. Jacks were delivered to prop up the cabin while the sill logs, or notched foundation logs, are installed.

While that is being done, archaeologists will sift through about six inches of topsoil in hopes of finding glass, metal, coins or any artifacts that could shed light on who might have built the cabin, what it was used for and how old it is.

They will take a cut from a sill log to compare its growth rings and patterns with those from other logs to determine when the logs were cut.

Based on Olson's experience, the notches carved near the ends of the logs are more akin to the style used after the turn of the century by someone who built the cabin without plans and limited skills.

Historian Louann Speulda-Drews of the Service's cultural resource team in Reno said not much is known about the cabin's origin.

"We think it was built in the 1880s or 1890s and used by outlaws or prospectors," she said on a hike to join the volunteers.

According to a paper she compiled, the cabin was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1975. The nomination form notes that it "is known to have been used by bootleggers during Prohibition and prospectors until around 1936."

But written records about the cabin site didn't exist until after the land was transferred to the Forest Service from the General Land Office in 1936 to protect bighorn sheep habitat.

No one filed a homestead patent or mining claim for it, "nor were there any neighbors or a nearby community that might supply a name or date for the cabin," Speulda-Drews wrote.

As for its legendary use by bootleggers, she wonders, "Why would you drive this far with glass bottles for moonshiners?"

She said remnants of stills, however, have been found at other rustic cabin sites in Southern Nevada, including one in Ash Meadows.

There is one solid connection to another cabin in the area: Railroad Tie Cabin near the Service's Corn Creek Field Station.

In the early 1900s, after Hidden Forest Cabin was built, ties from the Las Vegas-Tonopah Railroad were used to repair the cabin.

The railroad operated from 1906 until 1917 and a siding existed a mile west of Corn Creek when the railroad shut down. The ties are identical to the ties used for building Railroad Tie cabin at Corn Creek Ranch, according to Speulda-Drews.

In 1919, George and Clara Richardson lived at Corn Creek Ranch with their daughter and her family. The Richardsons' son-in-law, Perry Young, worked for the state highway department and brought many used railroad ties to the ranch for construction.

Speulda-Drews found that the Richardsons' 19-year-old son, Delbert, was a trapper, according to the 1920 census, and he might have used Hidden Forest Cabin as a seasonal residence for hunting bighorn sheep and trapping animals in the higher elevations of the Sheep Mountains.

"Of course, the cabin could have also been used by moonshiners, or perhaps Delbert was also brewing contraband liquor at the cabin," she wrote.

Prohibition was repealed in 1933.

Regardless of who might have built it or what it was for, the objective of the restoration effort is to extend the cabin's existence for another 30 years or longer and to preserve it as a destination for hikers, according to Olson's wife.

"That's what the goal is: to keep people enjoying this gorgeous setting," Joy Olson said.

Contact reporter Keith Rogers at krogers @reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0308.

Audio Slideshow