Teamwork, multitasking essential to operations at Nevada’s only Level 1 trauma center

In a hallway just outside the doors of University Medical Center’s trauma center, the words “Wall of Hope” rest above photos of recovering former patients.

The pictures celebrate the patients’ accomplishments, and the hospital hopes displaying photos of people who’ve survived life-threatening injuries can offer a semblance of encouragement to current patients and their families.

“We want the family members to walk by here and say, ‘You know what? There is hope,’” UMC spokeswoman Danita Cohen said.

But the photos are also a nod to the work of UMC’s staff.

The wall provides just a snapshot of what the hospital’s trauma center does every day, Cohen said.

“The big thing here is we never know what’s going to come through the door,” said registered nurse Jim Foley, just a few hours into a 12-hour shift on May 27, the Friday of Memorial Day weekend.

UMC’s trauma center, the only Level 1 trauma center in Nevada, can treat the least and most severely injured trauma patients. It serves a 10,000-square-mile region covering parts of Arizona, California and Utah.

The trauma center has a 96 percent survival rate for patients who arrive alive within an hour of the traumatic incident.

Foley, who mixes humor and compassion when engaging with patients, often monitors the radio, which alerts the staff to new cases from the heartbreaking to the absurd.

“You feel for them,” he said. “Then some of the folks come in, and you think, ‘Dude, what were you thinking?’”

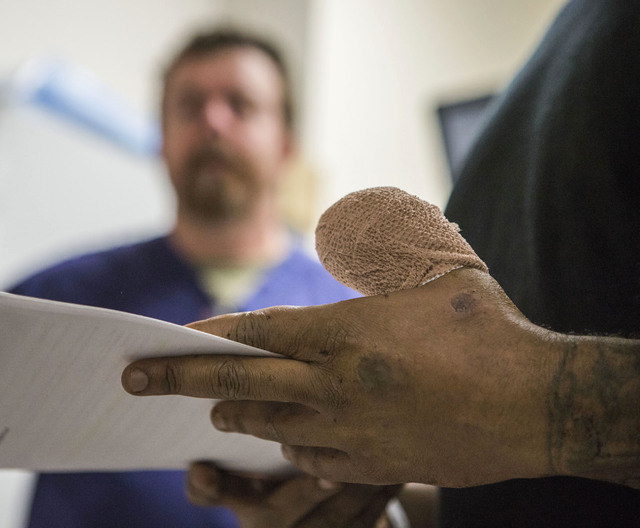

Lying on a bed near the rear of the trauma center, 36-year-old Dewayne Houston waited quietly to be discharged. Bandaging covered Houston’s thumb as Foley walked him through hospital paperwork.

When his finger got caught in a machine at the chocolate factory where he works, Houston was taken to a Henderson hospital, he said. When staff there couldn’t treat the wound, he was transported to UMC.

The tip of his thumb was cut off from the base of the nail and up. It couldn’t be reattached.

“It still hurts, just not as bad of course,” he said of the wound nearly two weeks later.

He complimented the care he received at UMC.

“They made me feel pretty nice,” he said.

Though UMC’s trauma center is generally busiest in the afternoon or evening, it takes only one bad moment for the quiet room to shift into a bustling crowd of nurses prepping patients, technicians performing tests and doctors overseeing the commotion.

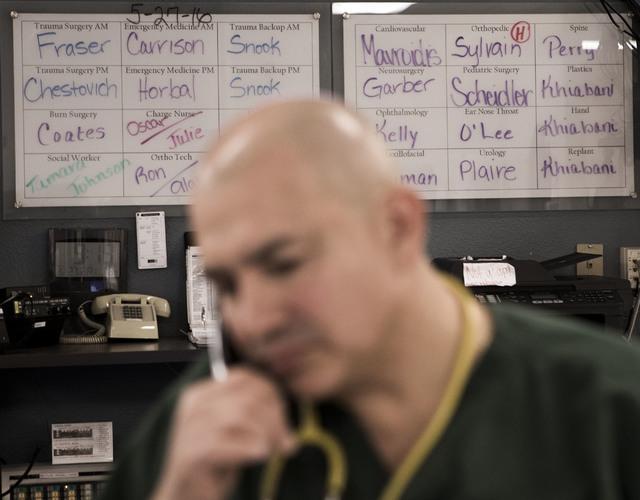

“Everything is ready to go, right here,” said Dr. Dale Carrison, chief of staff and an emergency medicine physician.

Carrison, a towering figure with a careful gait and watchful eye, has been with UMC for about 25 years.

Carrison is known for his for his bedside manner, but his diverse background may be what helps him get along with a wide array of patients.

Medical director of Las Vegas Motor Speedway, chairman of the University of Nevada School of Medicine’s Department of Emergency Medicine and former FBI agent, he instantly strikes up a conversation with able patients — asking them about their lives, work and families.

Jeff Smith, 58, said he was driving near Losee Road and Cheyenne Avenue facing a green light when a truck ran a red light. He crashed into the side of the truck, and an ambulance that happened to be nearby drove him to UMC.

Smith arrived inside the trauma center on a gurney, alert, wearing a neck brace and feeling lucky.

“It could’ve been a lot worse,” he said.

He and Carrison chatted about the former Nevada Test Site as Carrison checked to ensure Smith’s medications for Parkinson’s disease didn’t conflict with what the hospital was giving him.

“It’s good to meet you,” Carrison told him. “I’m sorry we had to meet this way.”

When the physician later sat back down to peruse patient records, he was joined by Jocelyn Ochoa, a 20-year-old College of Southern Nevada nursing student.

Ochoa, the daughter of Carrison’s longtime housekeeper, said she sought the doctor’s advice after she decided to enter the medical field. He offered her a chance to learn firsthand by allowing her to shadow him at UMC.

“How he speaks to them is a miracle,” she said of Carrison’s relationship with patients.

Carrison insists it’s just part of the job.

“The hardest part is what they’re going through personally,” he said.

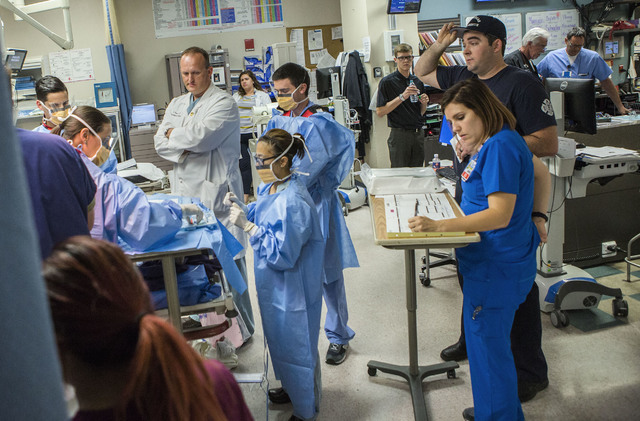

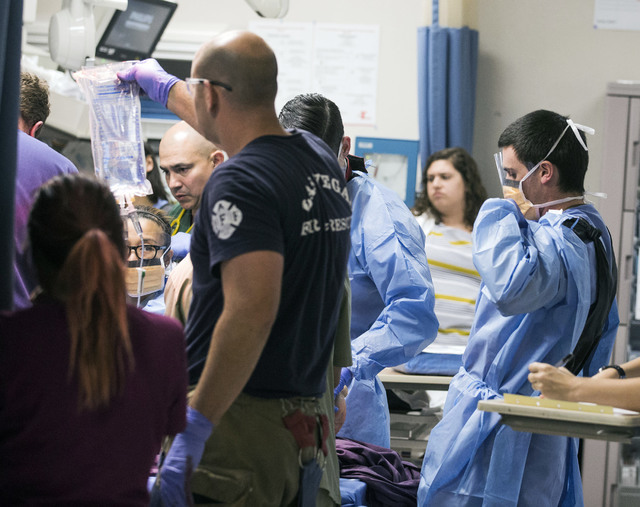

When a severely injured patient arrives, the trauma center breaks into organized chaos, Foley said.

It’s a point emphasized by Dr. Douglas Fraser, who made his way from the first-floor trauma unit to an upstairs conference room in the afternoon to quiz 15 medical students and residents on trauma care.

Fraser, a surgeon and the vice chief of the trauma department, is emphatic that UMC’s center is unique.

Trauma care at the Level 1 center requires multitasking and close teamwork for every case, he said.

“We’ve had nights where we have one after the next after the next,” he said.

Within a few hours of the class, he dealt with just that.

A helicopter landed swiftly and made way for another, and staff crowded around beds, awaiting the cases.

By then, patient volume had picked up. Seven of 11 trauma resuscitation beds were full.

Fraser calmly navigated a serious case, arms behind his back, marching alongside the bed as he encouragingly instructed staff.

Once that person was cared for, bloody sheets and equipment were tossed in the trash and staff members scattered to assist other patients.

Foley tried his best to make a nearby patient comfortable by telling jokes.

“I’ll close my eyes, you’ll close your eyes, we’ll see what happens,” he said with a needle in hand.

Behind a curtain, 45-year-old Scott Hill was also making people laugh, despite the blood on his face, the cut under his eye and the fact that the skin covering his nose appeared split in half.

Lindsay Wenger, the third-year general surgery resident stitching Hill’s nose back together, walked him through her work as it approached 7 p.m., the end of the workday for the first shift of trauma staff.

By then, Hill’s nose looked whole again. The bleeding didn’t stop him from telling his story of how an amateur mixed martial artist had caused the damage.

He said he was punched in the face, possibly with brass knuckles. He was found in a pool of blood at his home, and the Metropolitan Police Department responded to the scene.

“UMC, heck yeah,” Hill said within two weeks of leaving the hospital, after his stitches were removed. “I’m on their side. They were wonderful. I’ve had injuries in the past, but I’ve never had that kind of care.”

Fraser described trauma care as a team sport.

“We’re always prepared for your worst moment of your life,” he said. “That’s our average day.”

Contact Pashtana Usufzy at pusufzy@reviewjournal.com or 702-380-4563. Find her on Twitter: @pashtana_u

University Medical Center's trauma center has been spotlighted in Southern Nevada news recently regarding a debate over three trauma center applications filed in fall.

The Southern Nevada District Board of Health voted 7-2 Thursday to reject the applications for Level 3 centers filed by Centennial Hills Hospital Medical Center, MountainView Hospital and Southern Hills Hospital and Medical Center.

A trauma center with Level 3 designation can serve the least severely injured patients of incidents including car crashes and falls.

University Medical Center and its advocates argued most Level 3 centers are comparable to emergency departments and that approving new centers could take patients away from its county facility, the state's only Level 1 trauma center.

Several board of health members expressed concerns during and after the meeting that possible profits, not the public's best interest, may have motivated the applicants to vie for Level 3 designation.

Clark County Commissioner Chris Giunchigliani, who proposed the motion to decline adding additional centers, also asked for a possible independent assessment of the trauma system.

She said she'd like researchers to assess the trauma needs of the valley and determine if there's even need for a Level 2 center in Southern Nevada.

Sunrise Hospital and Medical Center, owned by MountainView and Southern Hills operator Hospital Corporation of America, is the only Level 2 center in the area.

The hospital was not immediately available for comment on Giunchigliani's remarks.

Centennial Hills has also declined to comment.

Bill Bullard, senior vice president of The Abaris Group, a health care consulting firm hired by HCA last year to assess the needs of the trauma system, argued that there was enough patient volume in the valley to support up to three, geographically separated level 3 trauma centers in the valley.

He also argued that the composition of the Regional Trauma Advisory Board, which advises the board of health in a nonbinding manner on center approvals, was innately biased because members are largely from existing trauma centers that wouldn't want competition.

The advisory board recommended against expanding the trauma system.