Former Indy 500 driver finds new, quiet life in Pahrump

PAHRUMP — The Pahrump Valley Speedway is to the Indianapolis Motor Speedway what a sandlot strewn with rocks is to Yankee Stadium. But when Richie Hearn showed up looking to race last summer, they still made him fill out a form listing his previous auto racing experience.

“I put down ‘Finished third at the 1996 Indianapolis 500, won the inaugural Las Vegas 500K,’ ” said the former IndyCar veteran. “They read that and said ‘This guy is full of (expletive).’ ”

Despite the audacious start to his open-wheel racing career, Hearn did not go on to become an auto racing superstar after his only victory.

And he never improved upon third place in his maiden voyage in the revered 500-mile race, which on Sunday will get the green flag for the 104th time with its massive grandstands devoid of fans because of the coronavirus.

Instead, Hearn embarked on what has been a long, strange trip to carve out a life for himself outside the sport.

Not worth the risk

It began when he finished 23rd in his last start at Indianapolis in 2007 in a car so evil he swore he’d never return. Better to walk away than be taken out on a gurney, he says.

He was 36 with half of his adult life still ahead of him — a reality that suddenly seemed more imposing than the unforgiving retaining walls at the world renowned speedway.

“After driving racecars my whole life, I realized I had no skills to get a job,” Hearn said.

He started a race team with the money he had earned driving.

“I should have just taken my money and bought some land in Las Vegas,” he said in retrospect of the venture that launched the career of 2016 Indy 500 champion Alexander Rossi before becoming unsustainable during the Great Recession. “I should have listened to my wife.”

Dark days

After he shuttered his team’s garage doors, Hearn fell into a financial abyss that ultimately cost him his marriage and soured him on the sport.

“I was literally rolling quarters. I bankrupted everything,” he said. “I was driving a forklift, working on a street crew — I did the striping on roads after they were repaved. I was doing all kinds of crazy stuff.”

He wound up coaching a flag football team.

He didn’t know anything about football except that his daughter wanted to be a cheerleader. When the head coach quit a week before the first game, Hearn diagrammed basic plays onto cheat sheets and called them out from the sideline. The team from Henderson made it all the way to the national finals at Walt Disney World.

But coaching youth football didn’t pay the bills, and it wasn’t long before Hearn found himself in a dark place. “I literally had nothing,” he said.

“It was pretty bad. I’m not going to lie. I went probably almost a year of literally doing nothing but feeling bad about myself. I went through a bad depression.”

Something’s cooking

The caution flag was out for Hearn.

“One night when I was drinking a lot, I saw a commercial for the Cordon Blue Culinary School,” he said. “I called the next day. My credit was terrible and I was like, there’s no way I’m going to be able to (afford) this. Sure as (expletive), the government gave me the money.”

It took him nearly two years to acquire an associate’s degree in the culinary arts. He got a job at Bobby Flay’s restaurant at Caesars Palace but found it unfulfilling.

“You’re just following a recipe and putting stuff in a fryer,” Hearn said, adding that if he had it to do over again, he’d just buy a food truck and be his own boss. “You’re not creating anything. I don’t need some chef screaming at me for eight hours just for the fun of it.”

But, he said of culinary school, “It kind of got me out of my funk. It gave me something to focus on and I was good at it. Even though I’m still paying off the school loan, I like to cook. I cook a lot, and it gives me self-fulfillment.”

As they say at Indianapolis, sometimes you have to let the race come to you.

When the Spring Mountain Motor Resort and Country Club opened in Pahrump, Hearn got a part-time job as an instructor. He was teaching racing during the day and cooking at night, then he black-flagged the cooking job because he liked teaching racing much better.

He is now lead instructor at the Ron Fellows Performance Driving School at Spring Mountain, a job that is right in his gearbox.

Familiar territory

“I don’t make a ton of money,” Hearn said during a recent day off. “I make enough. I like what I do; they treat me well. It would be great if I had some money to retire on, but I’ll probably work until I die.”

About a year ago he bought a new home not far from the auto racing country club. He’s only 60 miles from the bright lights of Las Vegas, but it seems farther, he said. Literally and figuratively. Hearn says he enjoys the peace, the quiet and the view of the nearby mountain peaks when they are covered by snow.

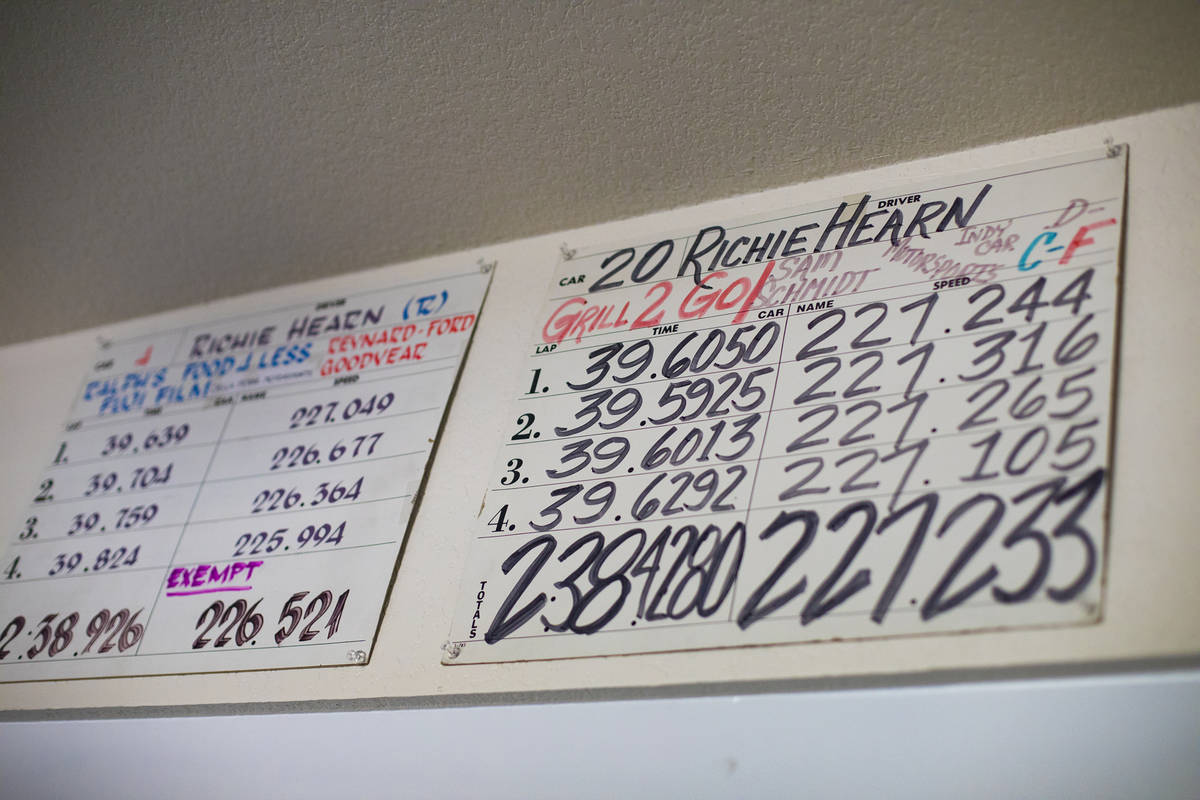

While he is proud of what he accomplished in auto racing — “I wasn’t the best, but I was pretty good at it,” he says — it no longer defines him. It has only been recently that he took some of his photographs and memories out of their boxes and put them on display in a spare bedroom.

Hearn drove in 84 IndyCar races over a career spanning seven seasons. He was loyal to his Argentine benefactor John Della Penna after they combined to win the 1995 championship in the stepping stone Toyota Atlanta series, a trait that probably altered his career trajectory.

After a string of strong runs in the CART series, Hearn turned down a full-time offer to drive for Bobby Rahal, the 1986 Indy 500 champion turned successful car owner.

“Richie is the classic example of a guy who did all the right things,” said Robin Miller, a member of NBC’s IndyCar broadcast team and perhaps the quintessential authority on IndyCar. “He was a really good guy and a good driver, and he was loyal to the guy who gave him his break. But going up the ladder of big-time racing, it probably cost him a career.”

After Della Penna lost his primary sponsor and ran out of money, Hearn essentially was relegated to one-and-done rides in the Indy 500, sometimes hopping into cars that nobody wanted to drive and sticking them into the starting field with white knuckle qualifying runs.

No regrets

“Richie was gold, an extremely talented driver,” car owner and Henderson resident Sam Schmidt said about the two teaming up four times at Indy, with a top finish of sixth in 2002. “Probably his only fault — and the reason he didn’t have a full career in IndyCar — was loyalty.”

Hearn doesn’t lose sleep over it anymore.

“I had some decent races, but we were always on the wrong motor or wrong chassis or wrong tire,” he said of an era in which having the right equipment was paramount to a driver’s success.

At 49 and with the roar of engines growing quieter, Hearn’s long, strange trip finally appears to be over. His relationship with the sport that nearly made him famous is minimal. He watches old Formula 1 races on YouTube but spends most his free time iRacing, engaging those who aspire to be like him in virtual reality races.

He says IndyCar racing is better and deeper than it has ever been, but doesn’t regret not being a part of it.

“I’ve done a lot of great things, gotten to go all over the world; I have a lot of good memories,” Hearn said as the gentlemen prepared to start engines at Indianapolis. “But I don’t miss it. I have my iRacing, and I go over to the dirt track and beat up on 15-year-olds.”

While that may be the polar opposite of running 220-mph laps with the legends of the Brickyard, he says it reminds him of when racing was fun.

Contact Ron Kantowski at rkantowski@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0352. Follow @ronkantowski on Twitter.